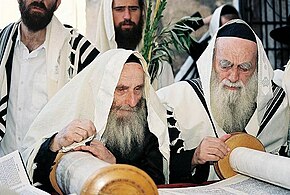

Os Haredi (em Predefinição:Língua com nome, translit. Yahadut Ḥaredit) são grupos dentro do judaísmo ortodoxo que são caracterizados por sua estrita adesão à halakha (lei judaica) e às tradições, em oposição aos valores e práticas modernas.[1][2] Seus membros são geralmente chamados de "ultra-ortodoxos", no entanto, o termo "ultra-ortodoxo" é considerado pejorativo por muitos de seus adeptos, que preferem termos como "estritamente ortodoxos" ou "haredi".[3] Os judeus Haredi se consideram o grupo de judeus mais religiosamente autêntico,[4][5] embora outros movimentos do judaísmo discordem.[6]

Em contraste com o judaísmo ortodoxo moderno, os seguidores do judaísmo haredi segregam-se de outras partes da sociedade até certo ponto. No entanto, muitas comunidades Haredi incentivam seus jovens a obter um diploma profissional ou estabelecer um negócio. Além disso, alguns grupos Haredi, como Chabad-Lubavitch, incentivam o alcance de judeus menos observadores e não afiliados e hilonim (judeus israelenses seculares).[7] Assim, as relações profissionais e sociais muitas vezes se formam entre judeus Haredi e não-Haredi, bem como entre judeus Haredi e não-judeus.[8]

As comunidades Haredi são encontradas principalmente em Israel (12,9% da população de Israel),[9][10][11] América do Norte e Europa Ocidental. Sua população global estimada é superior a 1,8 milhão e, devido à virtual ausência de casamento inter-religioso e uma alta taxa de natalidade, a população Haredi está crescendo rapidamente.[12][13][14][15] Seus números também foram aumentados desde a década de 1970 por judeus seculares que adotam um estilo de vida Haredi como parte do movimento baal teshuva.[16][17][18][19]

Referências

- ↑ Raysh Weiss. «Haredim (Charedim), or Ultra-Orthodox Jews». My Jewish Learning.

What unites haredim is their absolute reverence for Torah, including both the Written and Oral Law, as the central and determining factor in all aspects of life. ... In order to prevent outside influence and contamination of values and practices, haredim strive to limit their contact with the outside world.

- ↑ «Orthodox Judaism». Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs. Consultado em 15 de maio de 2019. Arquivado do original em 16 de maio de 2012.

Haredi Judaism, on the other hand, prefers not to interact with secular society, seeking to preserve halakha without amending it to modern circumstances and to safeguard believers from involvement in a society that challenges their ability to abide by halakha.

- ↑ Shafran, Avi (4 de fevereiro de 2014). «Don't Call Us 'Ultra-Orthodox». Forward. Consultado em 13 de maio de 2020

- ↑ Tatyana Dumova; Richard Fiordo (30 de setembro de 2011). Blogging in the Global Society: Cultural, Political and Geographical Aspects. [S.l.]: Idea Group Inc (IGI). p. 126. ISBN 978-1-60960-744-9.

Haredim regard themselves as the most authentic custodians of Jewish religious law and tradition which, in their opinion, is binding and unchangeable. They consider all other expressions of Judaism, including Modern Orthodoxy, as deviations from God's laws.

- ↑ «Orthodox Judaism». Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs. Consultado em 15 de maio de 2019. Arquivado do original em 16 de maio de 2012.

Orthodox Judaism claims to preserve Jewish law and tradition from the time of Moses.

- ↑ Nora L. Rubel (2010). Doubting the Devout: The Ultra-Orthodox in the Jewish American Imagination. [S.l.]: Columbia University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-231-14187-1. Consultado em 24 de julho de 2013.

Mainstream Jews have—until recently—maintained the impression that the ultraorthodox are the 'real' Jews.

- ↑ Waxman, Chaim. «Winners and Losers in Denominational Memberships in the United States». Arquivado do original em 7 de março de 2006

- ↑ «What You Don't Know About the Ultra-Orthodox». Commentary Magazine (em English). 1 de julho de 2014. Consultado em 8 de agosto de 2022

- ↑ https://en.idi.org.il/haredi/2021/?chapter=38439 Predefinição:Bare URL inline

- ↑ «שנתון החברה החרדית בישראל 2019» (PDF). Idi.org.il. Consultado em 2 de março de 2022

- ↑ «How many ultra-Orthodox live in Israel today, and how many in 40 years? These are CBS data». Hidabroot.org. Consultado em 2 de março de 2022 [ligação inativa]

- ↑ Norman S. Cohen (1 de janeiro de 2012). The Americanization of the Jews. [S.l.]: NYU Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-8147-3957-0.

Given the high fertility and statistical insignificance of intermarriage among ultra-Orthodox haredim in contrast to most of the rest of the Jews...

- ↑ Predefinição:Harvnb

- ↑ Buck, Tobias (6 de novembro de 2011). «Israel's secular activists start to fight back». Financial Times. Consultado em 26 de março de 2013

- ↑ Berman, Eli (2000). «Sect, Subsidy, and Sacrifice: An Economist's View of Ultra-Orthodox Jews» (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 115 (3): 905–953. doi:10.1162/003355300554944

- ↑ Šelomo A. Dešen; Charles Seymour Liebman; Moshe Shokeid (1 de janeiro de 1995). Israeli Judaism: The Sociology of Religion in Israel. [S.l.]: Transaction Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4128-2674-7.

The number of baalei teshuvah, "penitents" from secular backgrounds who become Ultraorthodox Jews, amounts to a few thousand, mainly between the years 1975-1987, and is modest, compared with the natural growth of the haredim; but the phenomenon has generated great interest in Israel.

- ↑ Predefinição:Harvnb: "This movement began in the US, but is now centred in Israel, where, since 1967, many thousands of Jews have consciously adopted an ultra-Orthodox lifestyle."

- ↑ Predefinição:Harvnb: "Many of the ultra-Orthodox Jews living in Brooklyn are baaley tshuva, Jews who have gone through a repentance experience and have become Orthodox, though they may have been raised in entirely secular Jewish homes."

- ↑ Returning to Tradition: The Contemporary Revival of Orthodox Judaism, By M. Herbert Danzger: "A survey of Jews in the New York metropolitan area found that 24% of those who were highly observant (defined as those who would not handle money on the Sabbath) had been reared by parents who did not share such scruples. [...] The ba'al t'shuva represents a new phenomenon for Judaism; for the first time there are not only Jews who leave the fold ... but also a substantial number who "return". p. 2; and: "These estimates may be high... Nevertheless, as these are the only available data we will use them... Defined in terms of observance, then, the number of newly Orthodox is about 100,000... despite the number choosing to be orthodox the data do not suggest that Orthodox Judaism is growing. The survey indicates that although one in four parents were Orthodox, in practice, only one in ten respondents are Orthodox" p. 193.

" class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="O que estudar para o enem 2023">

" class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="O que estudar para o enem 2023"> " class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="Qual melhor curso para fazer em 2023">

" class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="Qual melhor curso para fazer em 2023"> " class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="Enem: Conteúdos E Aulas On-Line São Opção Para Os Estudantes">

" class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="Enem: Conteúdos E Aulas On-Line São Opção Para Os Estudantes"> " class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="Como Fazer Uma Carta De Apresentação">

" class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="Como Fazer Uma Carta De Apresentação"> " class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="Como Escrever Uma Boa Redação">

" class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="Como Escrever Uma Boa Redação"> " class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="Concurso INSS edital 2022 publicado">

" class="attachment-atbs-s-4_3 size-atbs-s-4_3 wp-post-image" alt="Concurso INSS edital 2022 publicado">